CIF critical – understanding critical or important functions under DORA

One of the most consequential aspects of the Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA) is its emphasis on identifying and protecting what it calls “critical or important functions,” abbreviated as CIFs. This classification determines which systems, vendors, and data processes fall under the highest level of regulatory scrutiny.

Most financial institutions already perform business impact assessments and continuity planning, but DORA’s CIF framework introduces a stricter, legally binding layer. Once a function is labeled critical or important, it triggers specific testing, third-party oversight, and governance obligations. Failing to classify correctly could mean that essential systems remain unprotected and non-compliant.

What DORA means by critical or important functions

According to the European Banking Authority, a function is considered critical or important when its disruption would materially impair the financial performance, service continuity, or regulatory compliance of a financial entity.

This broad definition intentionally captures not only traditional IT systems but also outsourced services, payment infrastructures, and data processing activities that support core business lines. The aim is to prevent financial institutions from outsourcing risk while retaining only superficial oversight.

DORA’s language aligns with previous regulations such as MiFID II and the EBA’s 2019 Outsourcing Guidelines but expands their scope to include ICT-specific risks. It covers both operational dependencies and technology infrastructure, forcing firms to take a full-supply-chain view of resilience. DORA regulation explained: What it means for financial institutions

Why CIF classification matters

CIFs are the backbone of DORA’s proportionality principle. They determine where the heaviest compliance obligations apply. A bank’s mobile app, for instance, may not qualify as a CIF if its downtime has minimal impact on core operations. But the payment gateway that routes customer transactions almost certainly does.

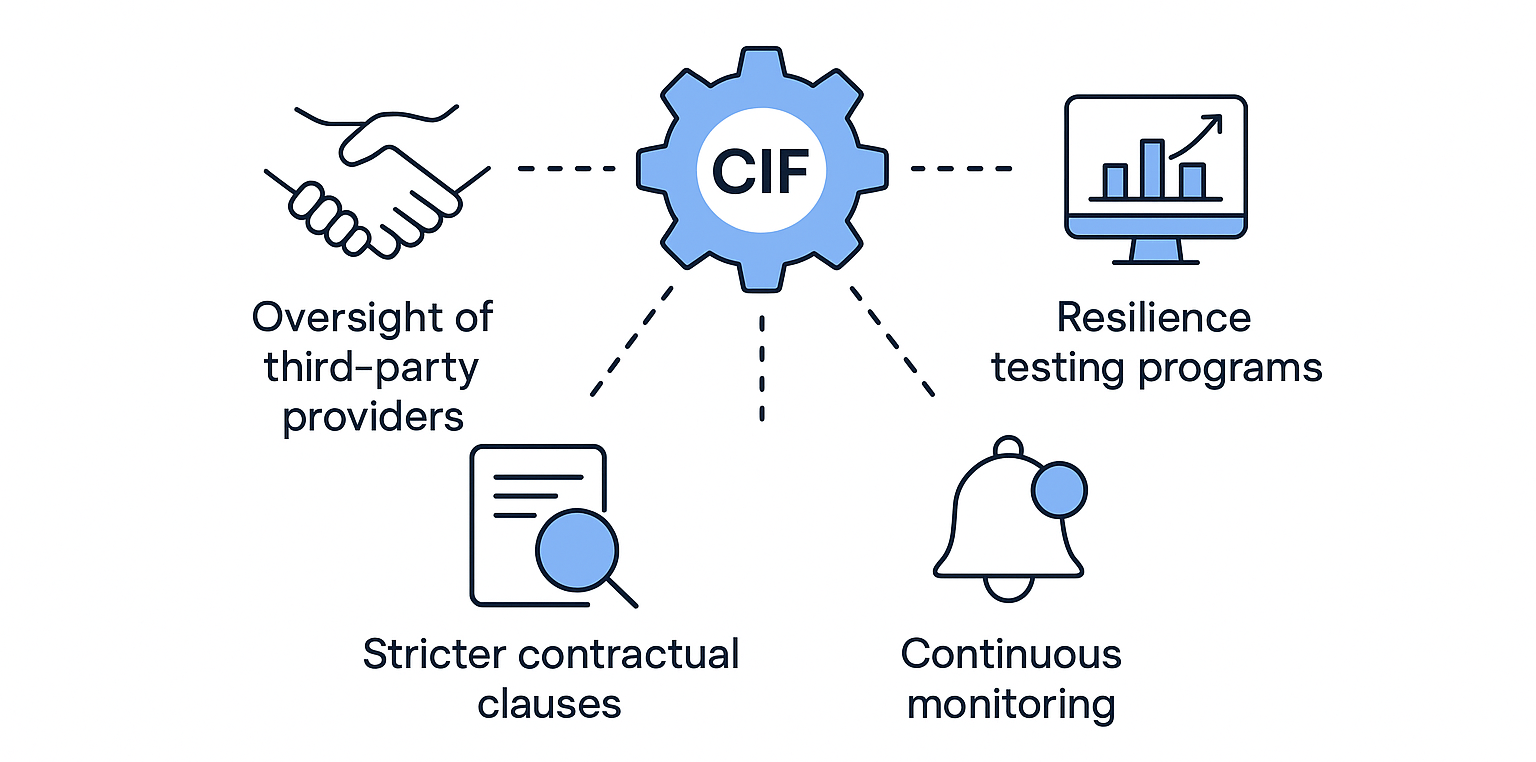

When an activity is labeled as a CIF, several obligations follow automatically:

-

Enhanced oversight of third-party providers involved in delivering or supporting that function

-

Stricter contractual clauses for audit rights, data access, and termination

-

Mandatory inclusion in digital operational resilience testing programs under Article 24

-

Continuous monitoring and incident reporting tied to that function’s risk profile

In short, CIF identification decides where DORA’s most demanding rules will land.

The process of identifying CIFs

Institutions cannot rely on intuition or legacy classifications. The CIF process must be structured, documented, and evidence-based. A typical CIF assessment involves five main steps:

1. Define the scope of operations.

List all business functions, processes, and supporting ICT assets. This includes both in-house and outsourced services.

2. Determine materiality.

Assess which functions, if disrupted, could cause financial loss, market disruption, regulatory breach, or significant customer harm.

3. Map ICT dependencies.

Identify the infrastructure, applications, and data pipelines supporting each critical process. Dependencies often extend across multiple vendors and geographies.

4. Evaluate outsourcing and third-party involvement.

For each external provider, assess whether its services are essential to maintaining operational continuity.

5. Document classification outcomes.

Maintain a register of CIFs with rationale, supporting evidence, and review dates. Regulators expect this documentation to be current and auditable.

According to NautaDutilh’s guidance, the CIF register must also identify ICT services that support those functions, ensuring no material risk is left unaccounted for.

Common pitfalls in CIF identification

Many firms underestimate how extensive their critical dependencies are. Functions that appear minor often rely on ICT layers considered essential under DORA. A good example is customer authentication. On its own, it might seem like a small technical process, but if it fails, every online transaction halts. That makes it a CIF.

Another pitfall is over-reliance on vendors’ self-classifications. DORA expects financial entities to take ownership of their own classification process. It is not sufficient for a cloud provider to claim its service is “non-critical.” The institution must assess and document that conclusion independently.

Finally, some firms attempt to limit the number of CIFs to reduce regulatory exposure. Regulators are aware of this tactic and have made it clear that under-classification will be treated as non-compliance. DORA RTS – regulatory technical standards

Integrating CIFs into governance and oversight

CIFs are not just a compliance label. They must be embedded into the governance framework and influence decision-making across departments. Senior management and boards are expected to know which functions qualify as CIFs and to understand their risk exposure.

CIFs should also drive how operational risk metrics are reported. For example, uptime, recovery time, and third-party performance indicators should be tracked specifically for CIFs. These metrics feed into Article 24 testing plans and incident reporting protocols.

Contracts with ICT third-party providers supporting CIFs must include specific DORA-mandated clauses. According to the European Commission’s implementing guidance, these include audit rights, access to relevant data, and exit provisions in case of service failure.

CIFs and third-party risk management

DORA treats outsourcing of CIFs as a special category of risk. It requires firms to maintain detailed registers of third-party arrangements that support these functions and to perform due diligence at onboarding and renewal stages.

The EBA has indicated that certain ICT providers may be designated as “critical” at EU level, bringing them under direct European supervisory oversight. This will apply primarily to major cloud service providers and cross-border data processors.

Institutions must also develop exit strategies for CIF-related third-party arrangements. If a vendor fails or withdraws service, there must be a documented process for business continuity and data recovery. These requirements will become part of routine supervisory audits from 2025 onward.

“CIF classification sounds like a paperwork exercise, but it’s the foundation of DORA. Without knowing what’s critical, you can’t design tests, manage vendors, or report incidents correctly. The regulators will expect clarity and evidence, not vague categories.”

– Mark Medum Bundgaard, CPO, Partisia

This statement captures what many regulators have been emphasizing: CIF classification is not theoretical. It defines the scope of an institution’s entire operational resilience strategy.

Are your business at risk of failing the FCA

FCA’s blockchain-enabled data strategy aims to save up to £4 billion in annual compliance costs source. Implementing Partisia’s MPC framework reduces duplication in cross-bank fraud checks.

What's inside?

-

Competitors & why Partisia prevails

-

Why Partisia exceeds industry alternatives

-

ROI & value proposition

-

Next step

and more...

The cost of getting it wrong

Failing to identify CIFs properly has cascading consequences. A misclassified function might not receive sufficient testing or vendor scrutiny, leading to vulnerabilities that are discovered only after a disruption. The resulting incident could expose the institution to both financial loss and regulatory penalties.

According to the European Commission, national competent authorities will expect institutions to present CIF registers and supporting evidence during inspections. Gaps or inconsistencies will likely result in supervisory findings and follow-up actions.

The cost of over-classification is mostly administrative, while the cost of under-classification could be existential. Most firms are choosing to err on the side of caution.

Privacy-preserving technology solves this

Identifying and managing critical or important functions depends on trusted data sharing between institutions and their third-party providers. Yet this is often the weakest link. Vendors hesitate to share operational data, and institutions struggle to validate resilience claims without breaching confidentiality.

Partisia’s privacy-preserving data collaboration platform helps solve this. Using Multi-Party Computation (MPC), institutions and their partners can jointly assess resilience metrics, simulate disruptions, and test recovery procedures without exposing sensitive data. Each party keeps its information private, while the combined computation delivers verifiable results.

This approach fits directly within DORA’s CIF framework. It enables financial institutions to demonstrate continuous oversight of critical functions and vendor dependencies through secure, transparent, and privacy-safe collaboration.

As DORA enforcement approaches, firms that can prove resilience through verifiable, privacy-preserving collaboration will not only meet compliance expectations but also gain a measurable operational advantage.

Looking to explore how privacy-first technologies can strengthen your AML efforts and support compliance. Get in touch with our team to learn how Partisia’s platform can help you collaborate securely while staying fully compliant.

2025.10.24